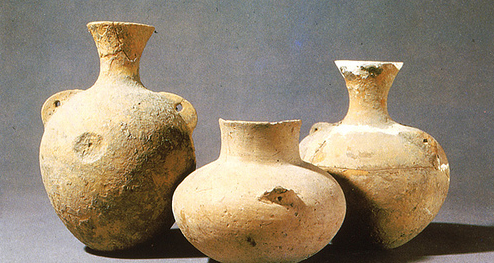

Early neolithic jars from Jiahu Province, China c. 7000 - 6600 BCE. Credit: University of Pennsylvania Museum

Early neolithic jars from Jiahu Province, China c. 7000 - 6600 BCE. Credit: University of Pennsylvania Museum

There’s something out there called the Biomolecular Archaeology Laboratory. It’s run by the University of Pennsylvania Museum and one of the things that keeps its inmates occupied is the examination of some of the oldest containers known for signs they once may have held alcoholic beverages. The idea is to determine when and where controlled fermentations were first induced and by whom. So far, the winners seem to be the Chinese for their chemically confirmed mash-up of of wild grapes, hawthorn, rice, and honey. This proto cocktail — for such it seems to be — was either shaken or stirred sometime around 7000 B.C.E. (give or take a happy hour or two).

It’s interesting that the earliest fermented beverages weren’t solely made from wine grapes but from a promiscuous mix of anything with enough sugar to produce alcohol. Perhaps the idea was to spread a buffet for yeasts that would raise the prospects of a quick, complete fermentation. Perhaps our neolithic forebears craved variety. Maybe they just couldn’t make up their minds.

By the time writing arrives a few millennia later, we’ve made a decision: we prefer our drinks differentiated. Wine shall be one thing, beer shall be another. Spirits come along much later, of course, but when they do we treat them separately, too. By now, it's a habit.

There are likely many reasons we determined that grapes were worth fermenting solo. One compelling factor: the very high sugar levels ripe grapes can achieve. Higher sugar levels translate into higher alcohols; higher alcohols help make a more stable (read: longer-keeping) beverage. In neolithic times, wine must have been an exceptionally fragile and transitory thing. In practice all wine eventually “goes off,” and we know that absent things like stoppered clay pots, tight barrels, and bottles with corks it goes off very quickly indeed.

Wine’s vulnerability to degrade is a clue that its making involves an interference with natural processes as much as a facilitation of them. This is because fermentation is just the first step in a more drawn-out project by which Nature intends to recycle fruit sugars not into wine, but into vinegar. From Her perspective, wine is just a stop along the way.

In one sense, the whole craft of winemaking can be seen as little more than a conscious interruption of this process - a self-serving attempt to trump Nature’s wishes and frustrate her purposes. Viewed this way, wine is merely a pause in an otherwise irresistible course of events — but one that from the beginning has engaged, pleasured, and refreshed us.

We’ve learned how to extend the life of wine by keeping at bay the microbes known as acetobacters that rob it of its vitality, but there’s only ever been one sure way of guaranteeing that that lovely grand cru Burgundy never becomes something fit only to dress the salad … and that is to drink it.

Stephen Meuse is a senior wine buyer at Formaggio Kitchen Cambridge, and regularly talks wine on local PBS affiliate WGBH with America’s Test Kitchen Radio host Christopher Kimball.