“What kind of wine is this?” is a question heard frequently in the Formaggio Kitchen Cambridge wine corner. Wine is categorized and merchandised so many different ways today that it's not surprising that consumers are confused by our attempts to simplify it.

One way to answer the question is to just look at how shelves in retail shops are arranged. In places where wines are heaped together by country, the response might well be “This is a French wine.” Other outlets shun the nation-state system in favor of a varietal approach, where the answer might be “this is a Chardonnay” or “this is a Cabernet Franc.'

Still others set a regional tack. In these outlets, Burgundy, Bordeaux, Tuscany, and the Mosel inhabit their discrete domains. Some retailers have sections devoted to wines made from organic grapes or wines that are low in sulfites. Wines with high scores from Robert M. Parker, Jr. or Wine Spectator magazine are occasionally given special accommodation. In these places, the answers could range from “this is a Cotes de Beaune” to “This is a 92 point Parker-rated wine.'

It’s not just wine shops that have to do battle with the categorization problem. Restaurant wine lists have to deal with it, too. Here, you’re likely to encounter the same range of alternatives (country, region, variety, color), but sometimes there are interesting twists. I first encountered an approach designed to facilitate food and wine pairing at Les Zygomates in the 1990’s when Lorenzo Savona organized his list under categories like “big, bold reds,” and “crisp, dry whites.”

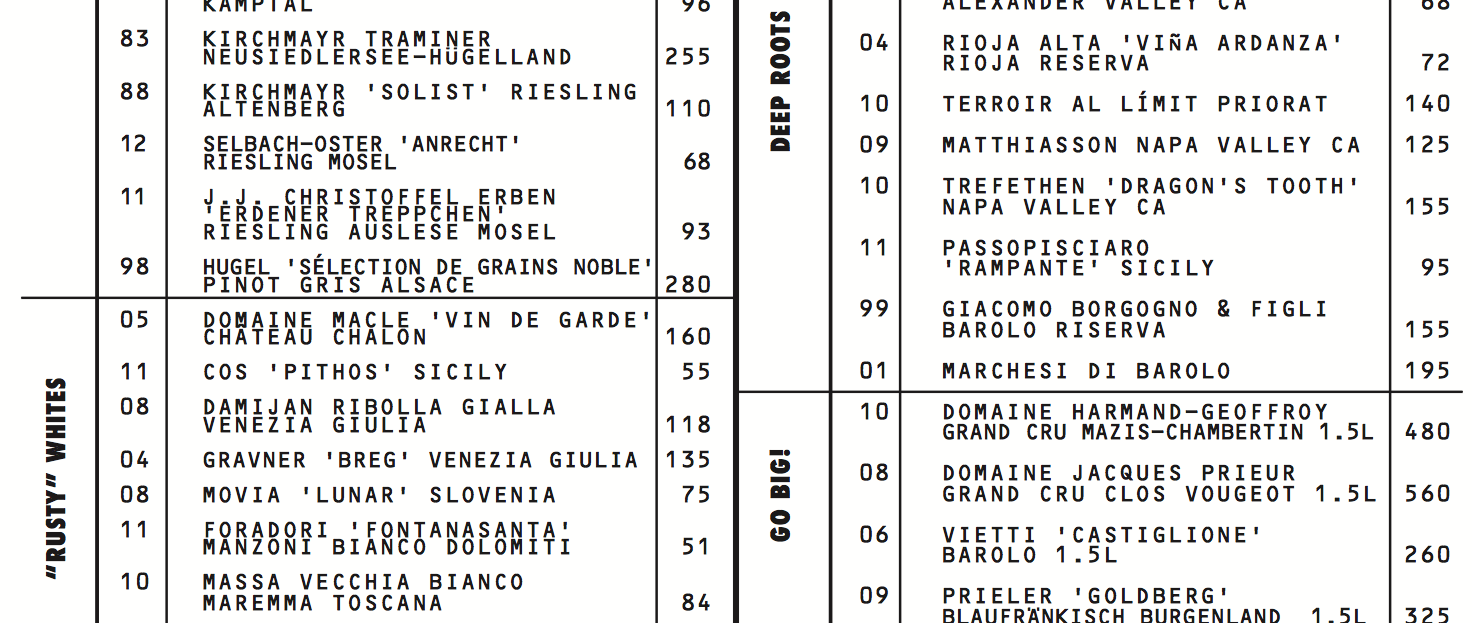

While this approach is relatively common today, it can still raise an eyebrow - especially when the categories aren’t what you’d call self-explanatory. At Kenmore Square’s Island Creek Oyster Bar, the wine list names “Rusty Whites,” which seems clear enough, alongside “Deep Roots,” which is a little harder to get a handle on (Ancient vines? Ancient varietals? Winemakers who never leave the farm?).

At Belly Wine Bar at One Kendall Square, owner and somm queen Liz Vilardi’s prodigious imagination is frequently seen off the leash. Categories on her current list include beach shades, driving goggles, and the inviting I want to go there.

In some sort of feedback loop, at least one wine shop known to me has adapted the trick for retail and arranged its shelves to create a progression from light to heavier wines, with the more muscular types farther from the door — possibly to discourage them from making a break for it. As an arrangement it doesn’t depend so much on conceptual compartments as on gradual shadings of temperament.

The way we organize wine in shops and restaurants is one thing, the way we organize them cognitively and in our speech seems to be another matter entirely.

For example, so-called natural wines constitute an important category today, even though it’s not really clear what these are or how we go about deciding which wines deserve the descriptor. The category is a legitimate one, but I’ve had to create sub-species to distinguish among the variations - not to say factions — that populate its ranks. I think of some in the movement as idealists, others as folklorists, primitivists, or cosmics. No doubt other shadings exist and only await a nomenclature.

But hang on a bit. There’s lots more. The technological, terroir, traditional, sacramental, and international wines, for a start. Authentic wines are a category, too, to judge from the literature, not to mention Parkerized wines, celebrity wines, and New Californians. There are organically and biodynamically-farmed wines from properties which are certified by some authority. Or not. Wild yeast-fermented seems important enough to constitute a category.

Say, have you got any vegan-friendly wines? Naked wines? Wines made in clay pots? How about high-latitude chardonnays? Reds that love a chill? Fireside companions? Glou-glou? In my days as wine columnist for the Boston Globe, I was once asked by an editor to write a story on “after-beach whites.”

Even in Les Zyg’s clever taxonomy the identity of each wine was front and center. How gobsmacked were we, then, on a visit to the then week-old restaurant Ribelle in Brookline when we saw that Teresa Paopao had furnished her list with descriptions (“light and pretty, delicate acidity, back-n-forth flavors of citrus-n-mineral”), but never revealed the identities of the wines described? That’s right, unless you press the server for the information or twist your neck around to get a peek at the label while she’s pouring it, you don’t actually know what you’re drinking.

In the Ribelle system, every wine seems to be a category in its own right, different in some however small way from every other wine on the list and, presumably, in the world. Seen from one point of this does away with the classification problem entirely - by just ignoring it. Maybe this is how it should be.

A key element of wine talk these days is the enduring, unchanging character of the land. It thrills us to learn that a family, like that of Marc Kreydenweiss in Andlau, Alsace, has been farming some of the same parcels (and living in the same house!) since the 16th century. The land stands still, and some families stay put, but both winemaking and wine consuming remain restlessly busy activities.

And as long as they do, you’ll have to forgive me if after pouring something at the tasting table, I pause long and thoughtfully over the innocent question: “What kind of wine is this?”

Author - Stephen Meuse is a wine buyer at Formaggio Kitchen Cambridge, and regularly talks wine on local PBS affiliate WGBH with America’s Test Kitchen Radio host Christopher Kimball.