At long last, natural wine is emerging from the shadows, coaxed blinking into the bright day of public wine consciousness by the diligent efforts of a handful of small-scale distributors, hole-in-the-wall retailers (we’ll put ourselves in that category), and the kind of wine bars where the demographic skews distinctly young and tattooey. It may still be a scarce commodity beyond the notional périphérique that encloses our city’s most ferociously hip zip codes, but a breakout into the banlieues is only a matter of time. So, exactly what is natural wine, and how can you know it when you see (smell, taste) it?

A good place to start is with a proposition or two. Let the first be that wine cannot make itself; it is wholly dependent on human agency and human ingenuity. In this sense, then, no wine is or can be a wholly natural product. It follows — as proposition two — that wine can only be thought of as natural in the same way that a novel can be a murder mystery or a movie can be a romantic comedy. In this context, “natural” is a classification: a shorthand way of referring to things that have enough in common to comprise a category. One way to know if a thing belongs in the category is to identify the elements generally thought to define that category and see whether a given thing ticks enough boxes to merit inclusion.

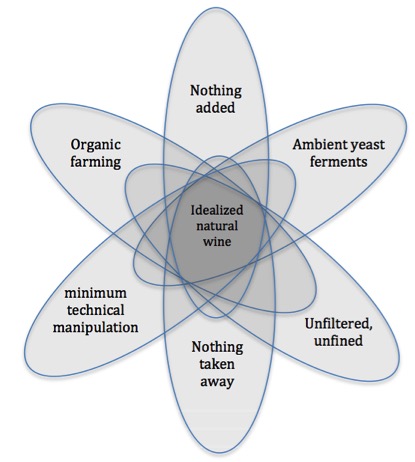

The Venn diagram above is one we created for an FKC wine class, with the aim of isolating a limited number of elements necessary for a wine to be called natural. Note that an organic approach in the vineyard is only one aspect - a starting point, let’s say. This alone does not qualify a wine as natural.

The rest of the diagram elements are concerned with how wine is handled in the cellar. Here, we would expect (1) a minimum of technical intervention - not much beyond a crusher, a press, vats, pumps, for example; (2) nothing removed from the wine or added to it (think yeast-nutrients, texture conditioners coloring agents, all summarized here as *off-farm inputs); (3) fermentation to take place spontaneously by yeast populations naturally present on the property; (4) the resulting wine to be left unfiltered and unclarified, except by the simplest mechanical means.

Note that styles of wine are not relevant for this classification. A wine isn’t “naturalized” by virtue of being made in small batches by an especially cute young couple, being a skin-macerated white (an orange wine), being fermented or matured in amphora, or bottled as a petillant naturel ( “pet-nat”). Biodynamic practices in the vineyard do not, by themselves, make a natural wine.

Theoretically, only a wine we can locate within the area where all the ellipses overlap would qualify as natural. In practice, this is rarely the case. There is, for example, the vexing question of sulfur dioxide, used since ancient times as a anti-bacterial and anti-oxidant agent. Does its use automatically disqualify as an off-farm input? We don’t see it that way, but we do expect any conscientious producer to be working on reducing reliance on it. The same applies to organic farming, which is relatively easy to accomplish in the warm, dry, sunny climate of Sicily, while being fiendishly difficult in Bordeaux where the humidity is ideal for the growth of molds and mildews.

No one makes and none of us drink idealized wine; and if there is a wine which exists free of moral compromise or financial constraint, we’ve yet to meet it. In this sense, natural wine may always be something more aspired to than achieved.

If you'd like to be introduced to the wonders of natural wine, come and see us in the Formaggio Kitchen Cambridge wine corner. You needn't appear au naturel, but it would be a powerful statement that you're serious about the subject.